Algorithms

The following section describe the different approaches for stitching the request graph to the container graph. Note that container graphs could be sub-graphs of larger container graph for performance reasons.

Full solution

This is the simplest way to stitch the request to the container graph. It starts by determining all possible combinations on how the request nodes can be stitched/mapped to the container. Iterating over that stitch/edge list it first eliminates all those candidates for which the type mapping is violated. Following that all stitches which do not meet the conditions are filtered out. A set of possible candidates is returned which can be validated further.

Obviously the Big O is not great, as time complexity is correlated with the number of possible combinations. The number of combinations is dependant on the number of nodes in the request and container. Some optimization has been done by using dictionary, and assuring most methods are lookups on dictionary instead of lists.

Evolutionary

The evolutionary algorithm for finding possible solutions uses a more darwinism based approach. Random candidates are created which are put into an initial population. Out of that initial population the best candidates survive, while the others die off. A candidate is defined by it’s genes. Whereby a gene set of a candidate represent it’s individual stitches.

Within the algorithm, first the best possible parents for new candidates are determined (default: best 20% of the population. This, like all others parameters is adjustable.). For diversity a certain percentage (default 10%) of the population is copied into the new population. New children are now created from this parent set using a crossover function. Following this a certain percentage (default 10%) of the children mutates. Overall the algorithm tries to keep the population size stable - this can be tuned to allow for growth or decay. The algorithm is finished when either a preset maximum number of iterations is reached, or the fitness goal is reached (default: 0.0). This allows for creation of multiple candidates (fitness goal != 0.0) and ensures the algorithm does not run forever when it dips into sub-optimal solution space and cannot reach the fitness goal.

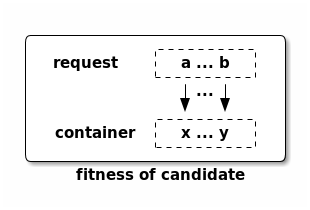

Each candidate contains a genes dictionary which represent the stitches - in the following example the dictionary would contain {‘a’: ‘x’, ‘b’: ‘y’}’:

The fitness of the candidate is determined by how good the stitches are. The sum of the fitness values for each stitch determine the candidate’s fitness (and ultimately the utility of the agents in a Multi-Agent System (MAS)). Stitches which do not adhere the conditions or type conditions get higher values for the fitness then those, satisfying all criteria.

The crossover function allows for combing the genes of a candidate with those of another and result in a new child. When doing the crossover the stitches with the best individual fitness value are preferred. This assures that the algorithm finds good solutions fast.

It is suggested to write more advanced fitness functions which eventually will obsolete the validation run as needed in the full solution approach. Making the validation step obsolete can be done by e.g. including the include the number of nodes & edges in the fitness value.

Mutation is done by randomly changing certain stitches to different targets.

The time complexity of this algorithms is obviously much better than working in the full solution space. By implementing specialized fitness functions it can be assured that the solutions found are ‘optimal’. Note however, that the algorithm might not always find a solution. Based on size and complexity it is necessary to tune the parameters introduced earlier to the use case at hand.

Bidding

The nodes in the container, just like in a Multi-Agent System 1, pursue a certain self-interest, as well as an interest to be able to stitch the request collectively. Using a english auction (This could be flipped to a dutch one as well) concept the nodes in the container bid on the node in the request, and hence eventually express a interest in for a stitch. By bidding credits the nodes in the container can hide their actually capabilities, capacities and just express as interest in the form of a value. The more intelligence is implemented in the node, the better it can calculate it’s bids.

The algorithm starts by traversing the container graph and each node calculates it’s bids. During traversal the current assignments and bids from other nodes are ‘gossiped’ along. The amount of credits bid, depends on if the node in the request graph matches the type requirement and how well the stitch fits. The nodes in the container need to base their bids on the bids of their surrounding environment (especially in cases in which the same, diff, share, nshare conditions are used). Hence they not only need to know about the current assignments, but also the neighbours bids.

For the simple lg and lt conditions, the larger the delta between what the node in the request graphs asks for (through the conditions) and what the node in the container offers, the higher the bid is. Whenever a current bid for a request node’s stitch to the container is higher than the current assignment, the same is updated. In the case of conditions that express that nodes in the request need to be stitched to the same or different container node, the credits are calculated based on the container node’s knowledge about other bids, and what is currently assigned. Should a pair of request node be stitched - with the diff conditions in place - the current container node will increase it’s bid by 50%, if one is already assigned somewhere else. Does the current container node know about a bid from another node, it will increase it’s bid by 25%.

For example a container with nodes A, B, C, D needs to be stitched to a request of nodes X, Y. For X, Y there is a share filter defined - which either A & B, or C & D can fulfill. Let’s assume A bids 5 credits for X, and B bids 2 credits for Y, and C bids 4 credits for X and D bids 6 credits for Y. Hence the group C & D would be the better fit. When evaluating D, D needs to know X is currently assigned to A - but also needs to know the bid of C so is can increase it’s bid on Y. When C is revisited it can increase it’s bid given D has Y assigned. As soon as the nodes A & B are revisited they will eventually drop their bids, as they now know C & D can serve the request X, Y better. They hence sacrifice their bis for the needs of the greater good. So the fact sth is assigned to a neighbour matters more then the bid of the neighbour (increase by 50%) - but still, the knowledge of the neighbour’s bid is crucial (increase by 25%) - e.g. if bid from C would be 0, D should not bit for Y.

The ability to increase the bids by 25% or 50% is important to differentiate between the fact that sth is assigned somewhere else, or if the environment the node knows about includes a bid that can help it’s own bid.

Note this algorithm does not guarantee stability. Also for better results in specific use cases it is encourage to change how the credits are calculated. For example based on the utility of the container node. Especially for the share attribute condition there might be cases that the algorithm does not find the optimal solution, as the increasing percentages (50%, 25%) are not optimal. The time complexity depends on the number of nodes in the container graph, their structure and how often bids & assignment change. This is because currently the container graph is traversed synchronously. In future a async approach would be beneficial, which will also allow for parallel calculation of bids.